Note: I received an email today from Al Scovern, a reader of this site and a long time listener of the podcast. Al wanted to pass a long the post below from his step-son, Cary Fontana, who is in Mali, West Africa, in the middle of a Peace Corps commitment. Cary does a great job of showing just how far Steeler Nation reaches and I am proud to post this story of his along with the pictures he included. Thank you to both Al and Cary for sharing this with the rest of Steeler Nation

By Cary Fontana

Steeler Nation extends a long arm. I mean really long. Bamako, the capital city of Mali, West Africa, is almost five thousand miles from Pittsburgh, the capital city of professional football. And while there are places on earth further from Pittsburgh when distance is measured in miles, there are few places further away than Mali when distance is measured in culture. I know, because for the past 16 months I’ve lived in a mud hut in the small village of Bilico. I’m a Peace Corps volunteer.

For most of the people in Bilico I am the only American that they’ve ever seen. They call me “toubab” or white person, with a mixture of curiosity, playfulness and, I think, affection. Most of the time, anyway. My Peace Corp mission here in Mali is twofold: to be a resident “ambassador” for the United States and to teach and facilitate sanitation and water purification. That’s my day job. My personal, classified, top-secret mission, however, is to conquer new territory for Steeler Nation.

Malians love football, it turns out. It’s the only sport ever discussed, and almost every man and boy has a team they support. On special game days my village, which has no running water or electricity, will use a gas generator or car battery to power an old, communal television. Homemade jerseys show team loyalty. Bets get made and taunts get exchanged. Malians can talk trash as well as any Steelers fan. Well, maybe not that well. Problem is, as much as they love their football, it’s the wrong kind of football.

Soccer, the short pants version of football, reigns supreme in West Africa. Before I arrived almost no one in Bilico had ever heard of the American version and so, as a special representative of American culture, I set out to bridge our cultural divide. A Nerf Vortex football helped. You know, the one with wings in the back that whistles when you throw it. This was an instant hit because almost anyone can make it spiral and the kids especially loved the whistling. That is, when they could snatch it away from their older brothers and fathers.

Teaching American football rules and strategy in Bambara, the language of my village, is, well, entirely hopeless. Take intentional grounding, for instance. Something simple to us, right? Intentional grounding is an incomplete pass thrown in an area where there is no eligible receiver. How do I describe “eligible”? I decided to put that on hold. Just stick with “no receiver” for now. Oh yeah, and then the quarterback (“Why do you say ‘quarterback’?”, someone asks) has to be in the tackle box (“You said that was your fishing case”, someone else says.) Oh boy. If the quarterback runs outside the tackles and throws where there is no receiver, then no grounding. Okay. But wait. In that case the ball still has to reach the line of scrimmage (“Scrimmage sounds French”, an angry voice says. “We don’t like the French?”). And here, I give up.

Foune, I’m the quarterback. Don’t let your brother knock me to the ground. Yes, stop him by any means necessary. Bakari, you run very fast to the goat. No, the big black goat and I’ll throw the ball to you and you catch it. What? Yes, then you run that way and don’t let anybody knock you down. Pardon? Yes, of course. First you catch it, then we’ll have tea.

Who needs rules anyhow? Steeler Nation isn’t about the purely technical– we leave the love of rules and strategies to teams like the Colts and the soulless Patriots. Steeler Nation is about history and tradition and Pittsburgh families now spread around the world. The Steeler diaspora, all the way to West Africa. But how to convey that history and that tradition? Language is still difficult. My Bambara is better each day, but still not adequate to convey something like:

“In the great kingdom of Pittsburgh, the center of everything right and good in America, there once lived a great man, a tribal Chief, named Art Rooney. During a trip to a neighboring kingdom Chief Rooney won a treasure in gold by placing a wager in a race of horses, and with that treasure he bought, as legend says, Pittsburgh’s football team. Some say that the Gods were displeased that he had acquired his fortune in a game of chance, and that they punished the great Chief by banishing his beloved Steelers to a dry desert of losing seasons for more than forty years. Lose though they did, word spread throughout the land of the Steelers great fierceness and courage on the field of battle. And it was on account of that courage that the Gods lifted their curse and sent to the Chief a brave and wise leader, General Chuck Noll, to guide the team out from the desert. And so he did. And the rest, as they say, is history.”

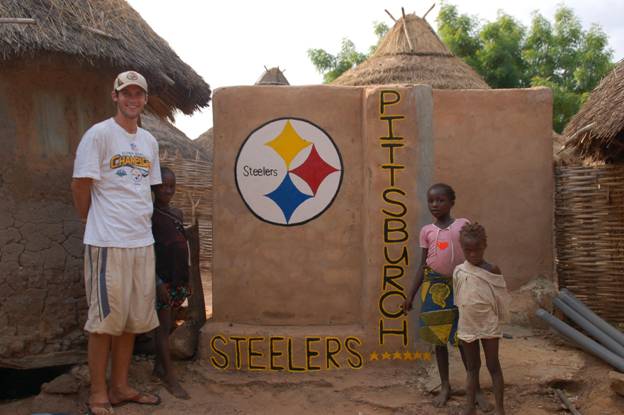

Too many words. With the help of my girlfriend, Emily Albert (also a Peace Corps volunteer), I came upon a better idea for story telling: murals. The plain, flat exterior walls of my latrine seemed to be the best if not most reverent place to start and the subject of my first mural was easy to choose. Our logo, which symbolizes our steel heritage and tough Pittsburgh workers and the Steelers all in one, is recognized world wide. Okay, maybe not world wide, but now, at least, in a remote corner of West Africa. Note the game faces on these young fans. As all of Steeler Nation understands, it’s never too earlier to start the indoctrination.

As a toubab, the inhabitants of my village naturally find most things that I do somewhat strange, and so my behavior is often the focus of curiosity. Watching Emily and I paint in near hundred degree Sahel heat, amid swarms of giant flies, was itself cause to think we were a bit loco, but we regarded it as an opportunity to demonstrate Steeler Nation fortitude. Many people came by, of course, to inquire just what it was that we were doing, which I took, naturally, as an invitation to tell them about the greatest franchise in professional football. In all of professional sports, in fact. And not just in the United States but throughout the world. Probably throughout the whole universe, I said, and they replied, in proper Bambara, that perhaps I exaggerated. Perhaps, I conceded, but who could argue with six world championships. Six. Unprecedented. And then they asked just how these could be “World” championships if American football was not played around the world, and I said that there were just some things too complicated to explain with imperfect Bambara.

Still, they were impressed with six championships. They understood, through their knowledge of soccer, just how difficult it is to win a professional sports championship and so this, I felt, needed commemoration with a mural as well.

As you can see, between mural one and mural two (many thanks to Emily for the art work—I’m more of a concept guy) the Steeler fan base in Bilico more than doubled.

I’m asked about the players. What are their names? How big are they? Roethlisberger is hard for them to say, but I make them practice. They like the sound of Polamalu. Who doesn’t? I showed them a picture of James Harrison and they asked if he was mean. I told them that while he played very hard, that he was a warm and engaging man. I had some fingers crossed at the time. Who is your favorite player, they ask. This is hard. There are so many. Big Ben, the monster Woodley, the underrated Heath Miller, Troy of course. But then it’s not so hard. It always gets back to number 86, Hines Ward. The heart and soul, a Steelers’ Steeler. A guy even Jack Lambert would be proud of. So now Steeler Nation-Mali loves Hines Ward too.

Strangely, perversely even, I’ve seen quite a few Baltimore Ravens jerseys being worn by Malian men. A Peace Corps volunteer from Baltimore who lives about 3 kilometers away decided to play a practical joke on me by distributing Ravens jerseys to my villagers on a day when I was away. Actually pretty clever. I didn’t hold it against my villagers—they are very, very poor and they take what they can get, and besides, they had no idea what they were wearing. And, of course, that great surplus of unused, unwanted Ravens gear in the U.S. has to go someplace, after all.

Malians can be wonderful people. They are warm and welcoming and incredibly generous with what little they have. To put their poverty into perspective, the GDP for Mali in 2010 was about 16 billion dollars. The combined NFL player salaries for 2009-10 totaled more than 3 billion, about 20% of the entire country’s GDP. Put another way, the average annual income for Malians is somewhere between $800-1200. That’s per year, making it somewhere in the ballpark, I’m guessing, of the cost to equip one NFL player for one game. Sometimes, here in West Africa, it is possible to think that it’s not just that they have too little, but that we have too much.

Anyhow, these are my people now, newest additions to Steeler Nation. I’ve worked hard to recruit them. I hope that you’ll welcome them.