Well, I thought if I wound up writing about the Pittsburgh Steelers‘ 2015 2nd round draft choice, Senquez Golson, who missed his entire rookie season, it would be to discuss the durability of his shoulder after his labrum was repaired last year. As it turns out, he only made it through 3.5 training camp practices before hobbling off the field with what the team would initially call a “mid-foot injury”. At which point every knowledgeable fan began to worry about a dreaded Lisfranc injury. Later that week, head coach Mike Tomlin confirmed that the young cornerback did, in fact, have a Lisfranc injury. It is not yet clear – or at least they aren’t yet telling us – if Golson will require surgery.

The general consensus is that Golson will miss at least 3 and possibly 4 months. This would mean that his earliest return to practice would be late in the season…unlikely that a virtual rookie with no training camp experience or preseason play will make his debut when the Steelers will hopefully be making their push for the playoffs. Sadly, his second season will likely be a total loss.

So how could such a small injury cause such major problems? Let’s take a look at what may be the least understood injury, but one that is becoming more common each year.

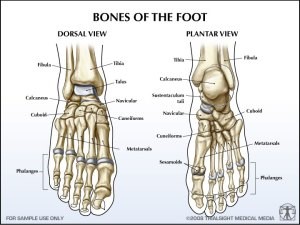

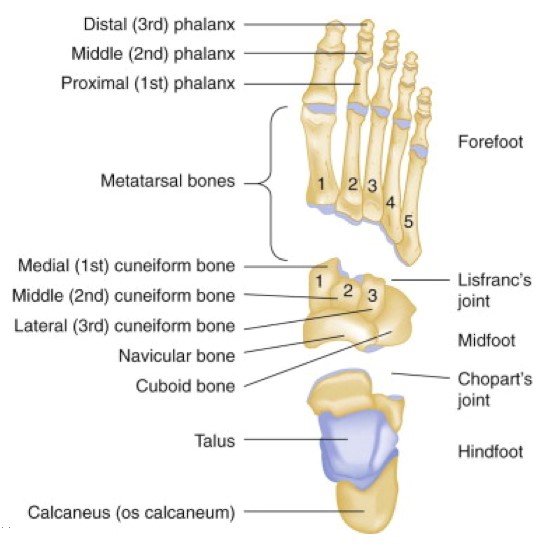

First, a review of the foot’s anatomy:

(Note: the dorsal view is from the top of the foot and the plantar view is from the bottom)

(diagrams from www. vo2maxproductions.wordpress.com and www.emdocs.net)

The foot is broken up in sections. The forefoot includes the bones of the toes (phalanges) and the long bones (metatarsals). The midfoot contains a collection of bones that make up the arch (the cuboid and cuneiform bones), and the hindfoot is the heel (the talus and calcaneus). There are ligaments that hold all the bones together…with one exception. There is no ligament between the 1st and 2nd metatarsal, which adds increased flexibility to the joint but also leaves that part of the foot more vulnerable.

Most weird anatomical names come from the physician or surgeon who originally described it, and that is true of the Lisfranc joint. Jacques Lisfranc was a field surgeon in Napoleon’s army. A soldier fell from his horse but twisted his foot, which was stuck in the stirrup. Lisfranc had to amputate the soldier’s forefoot due to the injury (fortunately, we have better options these days!), and he chose this joint as the point for transection.

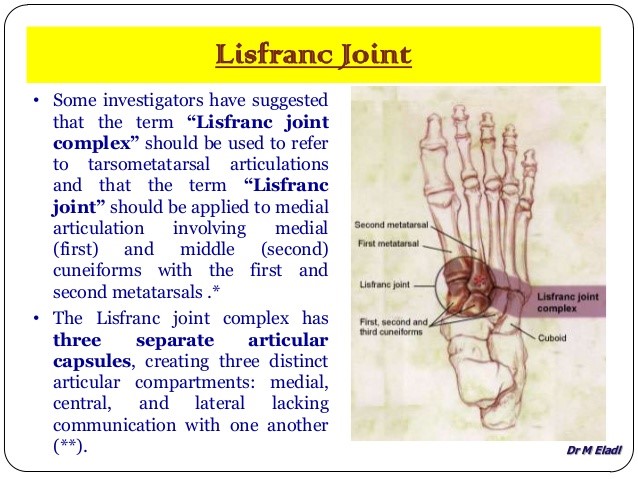

This slide was part of a presentation by an assistant professor at the University of Sharjah in the Emirates, and it shows why the Lisfranc injury is so confusing because there are so many different points of contact between the bones, and the type of Lisfranc injury depends on which part of the joint complex is involved:

On top of that, a Lisfranc injury ranges from a torn ligament (sprain) to a fracture and even dislocation. A Lisfranc injury can often be mistaken for a simple sprain at first. But it is different from a regular sprain because even with the mildest form of a Lisfranc injury, there is joint instability where the forefoot and the midfoot articulate, or bend. Even with just a Lisfranc sprain, you can see widening of the joint space between the 1st and 2nd metatarsal bones. And even without a fracture, there can still be significant dislocation of the bones, as you see in these Xray images from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons:

The first Xray shows a normal left foot and a widening the 1st and 2nd metatarsal joint space in the right foot due to a Lisfranc sprain. The middle Xray shows a fracture of the 2nd metatarsal (indicated by arrow) and the cuboid bone (in circle), where the bones are no longer aligned correctly. The right Xray shows a severe injury with complete dislocation of the entire midfoot, even though there are no actual fractures. This patient will certainly need surgery to realign those bones and possibly even a fusion of the midfoot.

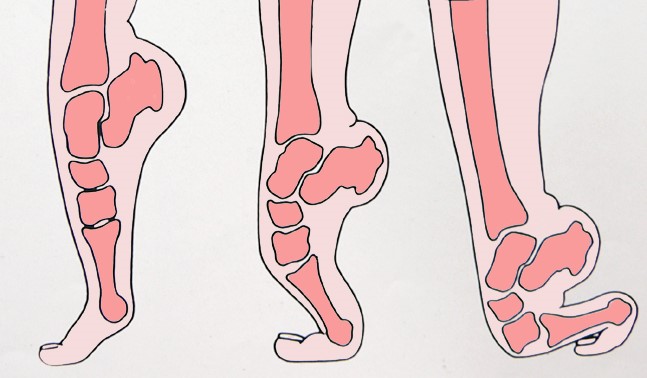

How does this injury happen to NFL players when they aren’t riding horses in Napoleon’s army, you ask? Most NFL players don’t sustain high velocity injuries, as in a fall from heights or a car accident. Instead, the most common mechanism of injury is a low velocity injury (which can still result in a mechanically significant disruption of the Lisfranc joint) that comes in one of two forms:

- The first mechanism is plantar flexion with axial load. We saw this when QB Ben Roethlisberger’s foot got squashed by the weight of Raiders Aldon Smith during a sack.

Fortunately, Big Ben was only diagnosed with a “midfoot sprain” but not a Lisfranc injury. And no, I can’t tell you how the team doctors determined the difference.

- The second low velocity mechanism is forced abduction of the forefoot, and this is probably what happened to Golson. It is a non-contact injury and most commonly occurs when the athlete plants his foot in a cleated shoe and turns quickly, applying stress to the middle of the foot.

The diagnosis of a Lisfranc injury is made by physical exam and Xray. Swelling of the midfoot as well as bruising on the both the dorsal and plantar surfaces is common. On Xray, joint abnormalities can be identified. MRI is not necessary to make the diagnosis, but it is the best way to diagnose specific ligament tears.

So what does it mean when the Steelers say Golson may have surgery but it hasn’t been determined yet? I’m speculating here (cue arguments in comment section and on twitter), but I would guess that Golson doesn’t have a fracture because that would almost certainly be an indication for surgery. It is possible that the team doctors are waiting for the swelling to go down to get a better idea of how much joint instability the CB has. Then again, never count out the Steelers tendency towards being super secretive about injuries. They may have already decided that Golson needs surgery – heck, maybe he already had it done – and they just aren’t telling us because they don’t have to, the same way they held back updates on Center Maurkice Pouncey last year…who had a total of 7 surgeries, as it turned out, and we only sort of knew about 2 of them.

If Golson does require surgery, he will probably have some screws and plates placed in his foot to stabilize the joint and allow it to heal in the proper alignment. The hardware usually gets removed with a second surgery further down the road. Here is an example of what it might look like:

(Schematic from www.officiallytoons.com and Xray from www.aofas.org)

If he does not require surgery, typical treatment is immobilization with a cast and strict “no weight bearing” on the foot (i.e., crutches) for 6 weeks. Following that, the patient progresses to weight bearing in a removable boot. Depending on healing, gradual increase in activity is then attempted. Recovery from surgery is fairly similar in terms of timing, but the patient is restricted from running and jumping until the hardware is removed, which usually occurs 3 to 5 months after the surgery.

What is the potential for recovery? Unless the joint is so damaged that it requires fusion, most NFL players can return to the field. That’s the short answer. The long answer takes quite a bit more explaining, so look for it in my next post (shameless teaser)…